Over the last six years, violence has sporadically burst out in Tripoli’s impoverished neighborhoods. Walking the narrow alleys, one starts to feel the ongoing discontent of angry men who, like glowing embers, constantly flare up in conflict. Whether it is through political-sectarian agitation and/or the work of manipulation by local politicians, people remain hostage to their wretchedness. After years of political violence that has engulfed the poverty-stricken neighborhoods, a broken and alienated youth embittered by their politicians has emerged. Though much was been written to report on the violence in Tripoli, less has been written about the social fabrics and everyday experiences of Lebanon’s second capital.

On 24 October 2014, following Friday prayers, armed militiamen in Tripoli took to the streets in response to calls made by Shaykh Khalid Hubals and Shaykh Tarek Khayyat for an armed insurrection against the Lebanese army. Both shaykhs gave fiery speeches on that Friday accusing the Lebanese military forces of “implementing security only against Sunnis.” In addition, both shaykhs urged Sunnis in the Lebanese army to defect. Following Friday prayers, the armed militiamen spread out holding positions in the fortified streets of old Tripoli. Another prominent Sunni shaykh backed by Saudi Arabia, Da`iyya al-Islam al-Shahal, warned the Lebanese security apparatus against applying emergency security measures in the Bab al-Tibbani area. Instantly, the battle fiercely ignited against the Lebanese army in Tripoli. Later on in Akkar of northern Lebanon, calls for a “Sunni uprising against injustice” exacerbated the situation. The Lebanese army responded by entering the battle in Tripoli and Akkar, dubbed as “the toppling of the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra’s emirates in the north.” Three days of clashes left twenty-seven people dead and heavy building damage in the historic market of the city. The battle ended, but the war in Tripoli and northern Lebanon continues to escalate. Local militants from Tripoli who claimed allegiances to Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State disappeared but did not vanish. This was another round of killing and destruction in Tripoli that has grown to be part of the routine in the city for the last six years; each round claiming innocent lives and livelihoods.

The Priest and the Library

[The entrance of al-Saeh, a historic wooden door tucked beneath the arches

in a dim alley in the historic city of Tripoli. Image by author.]

Seen through the eyes of reductive news reports, Tripoli’s image seems distorted. In order to imagine Tripoli and also get a sense of the depth of its culture one needs to dip deep and rub shoulders with its many layers that make up the different communities. Walking through the many layers that make up the different communities, I stumbled upon one of Tripoli’s many treasures. It was there that I walked into the biggest library I had ever seen in Lebanon. The well-carved ancient pathways where I found the library were designed to fortify the old city in the face of invading armies. This might seem the reason why the latest battle with the Lebanese Army originated in Tripoli’s old suq. The loose bands of Islamist militants were protected by the narrowness of the alleys which prevented the entry of armored vehicles and facilitated cover for ambushes… The ancient market is a maze of narrow alleys that melt beneath arches connecting decrepit historic buildings that have been steadfast despite the waves of gentrification disfiguring Lebanon. The interwoven network of alleys leads to Khan al-Sabun (the soap market), and then down to the coppersmith market that stands right next to the street of libraries. Tripoli’s popular market supplies affordable commodities to low-income residents. The integral hustle and bustle of this historic landmark never fully dissipates, but is often dominated with a different kind of hustle in times of armed clashes. Then, the rumble that dominates the market is the sound of bullets by warring factions whose actions and motivations vary (e.g., clans feuding over personal/political interest and allegiances, Islamists fighting the army, sectarian attacks against ‘Alawi-owned businesses). In the absence of functioning state institutions such as army or police people and politicians tend to settle scores their way.

Down at the end of libraries’ street, al-Saeh Library still stands. One of the largest libraries in Lebanon that fell victim earlier this year to a fire of conspiracies that ravaged its vast archive of books (and knowledge) stacked on its shelves. Owned and founded by Greek Orthodox priest Father Ibrahim Sarrouj in 1972, the library shelves held over seventy thousand books of various genres. When I visited the white-bearded Father Sarrouj dressed in a ragged laborer’s outfit stained with splashes of white paint, the dusty bespectacled priest was immersed in the rehabilitation work his library has since been undergoing. We sat between piles of books that reached the five-meter high arched ceiling, one half of which was freshly painted white and the other half of which remained charcoaled. “Before the attack that burned down parts of my library I used to have 85,000 titles. The arson damaged eight thousand titles, but I do not care. We will retrieve them.” The priest said he was full of enthusiasm when people flocked to the library to manifest their solidarity “against this terrorist act.” The library, the “love of his life,” was attacked on 2 January 2014. Two men on a motorcycle shot at Bashir Hazzour, a new employee who had just started in the library. “He was hit and wounded by seven bullets,” said Sarrouj. The evening of that same day, the conspiracy against the library started. A text message circulated on phones in Tripoli with the name of another priest called Father Jarous. “They confused my name with this man [Jarous] who allegedly made some comments against Islam. They also printed and posted the circulating statement in front of Mansouri mosque, one hundred meters away from the library. Provocateurs started agitating by spreading this rumor,” recalled Sarrouj. The library was set on fire soon after. Following the arson, the undeterred priest discovered the actual reason behind the attack on his library. “It was the owners of the building,” he said. “They wanted to sell the building after the municipality classified this building as a historical site. Consequently, the owners could not sell it and had to restore it instead.” In addition, Sarrouj reached out to the Mukhabarat (intelligence service) who arrested one of the five people involved in the arson. “The culprit confessed that one of the building owners gave him two thousand dollars to burn down my library—not only to burn the books but to burn the whole building and destroy it. The owners’ financial interest was one motive for the attack. The other motive I found out about was to create fitna (sedition) between communities in the old city. These two groups found common interest against the library and conspired against it.”

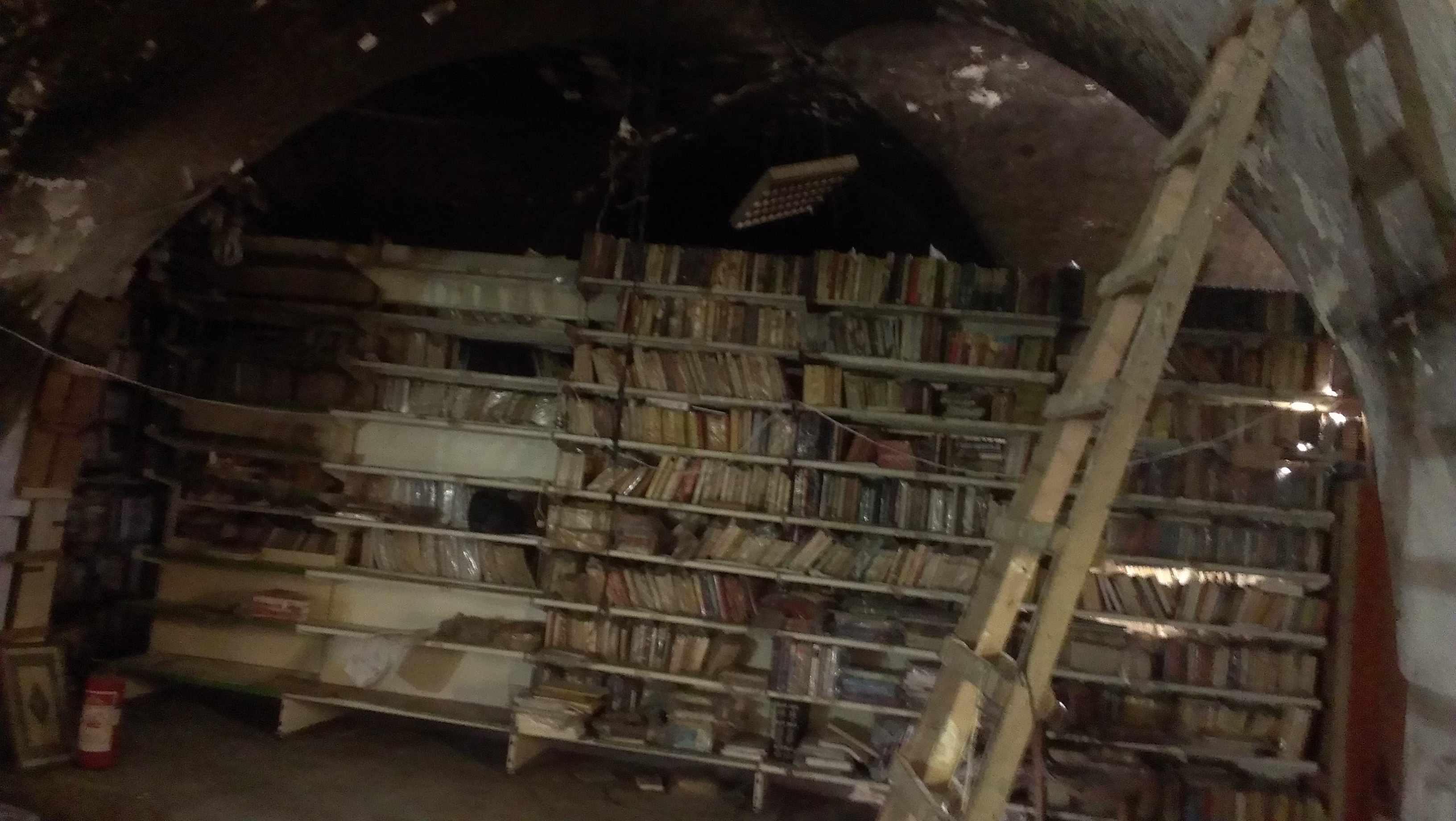

[Under construction inside the library: remnants of the wreckage caused by the arson that

targeted the library in January 2014. Image by author.]

Sarrouj says that all kinds of books are welcome in his library:

We have English, Arabic, French, Germen and Italian titles. I have books on philosophy and theology for Muslims, Christians, ‘Allawis, Sunnis, Shi‘is, and all kinds, even astrology books. This library is a space that promotes coexistence between our communities; priests, shaykhs and Marxists come here to buy their books.

The old librarian is one of the few Lebanese who still believe in coexistence between communities in Lebanon. He argues that living together “is a reality and those so called terrorists are a minority—a weak minority among Muslims and Christians.” As for the violence perpetrated by young men in Tripoli, Father Sarrouj knows it is “certainly the work of both political manipulations on top of harsh socioeconomic realities.” He argues that, “These two elements are a recipe for chaos; deprived ignorant youth easily mobilized with few words by some opportunistic representation of Islam. The misuse of some words can easily agitate and spread violence. Put some money on top of it and it is immediate.” Ultimately, he agrees that the main factor is the nonexistent state institutions, “No doubt, we have been neglected by our state for a long time now in Tripoli, Akkar, and all over Lebanon. We do not have real politicians, we have businessmen.”

As well as working to restore his library, the busy old priest also works to restore relations between the various communities that make up the half a million citizens of Tripoli. “We are an authentic community still alive in our Muslim city of Tripoli, coexisting with other Christian minorities such as Maronites, Greek Catholics, some Protestants. There are also Jehovah witnesses.” On the latest media fanfare of the jihadi threat toward Christians in the region, Sarrouj proclaimed: “We have inhabited Tripoli since time immemorial therefore we do not fear the so-called jihad threat. Some Christians exaggerate this threat so they can go to Europe and cry it out in front of the church. There is some concern in regards to Christians in Syria and Iraq yes, but not here in Lebanon.”

[Piles of books stacked in the backyard of al-Saeh Library. They are part of the vast archive

waiting for renovation work to finish inside the library. Image by author.]

The School vs. the Streets

The recent clashes between Lebanese security forces and militants loyal to Jabhat al-Nusra and IS were a foreseen development in Tripoli. Throughout the month of October 2014, mosques in Tripoli called for protests in response to the announcement that Hizballah’s participates in the ongoing clashes between the Lebanese army and militants from IS and Jabhat al-Nusra in Brital and ‘Irsal’s mountain terrain north of the Biqa‘Valley. The “Hizballah-Lebanese army alliance against the Sunnis” has been a mantra for the last three years at least. It was first propagated by Sunni politicians in the 14 March Coalition on the airwaves, and later became a conviction by many on the Sunni street. The figures that initiated and led the war against the army in Tripoli are well-known emerging figures, Islamist firebrands. On a hot summer night, LBCI news channel aired an interview with the emerging two young Sunni enthusiasts. Abu Omar Mansour and Shadi Mawlawi declared, from their stronghold area of Bab al-Tibbani, “We are close to al-Nusra Front in terms of policy, ideology, and practice. We love the al-Nusra Front, but we have not pledged allegiance to it or to the Islamic State.” Following the interview, many upper class Lebanese—ensconced in their bubble—were baffled and squealed in horror, “Where is the Lebanese government and why do they not arrest them?” However, many Sunni youth in impoverished pockets across Lebanon fired their guns in jubilation and support of the young zealots. That is precisely the difference: the severe poverty in Tripoli has freed young people from caring about “society’s” opinion, pushing them to the most radical of expressions just as money has freed rich politicians’ children from knowledge of anything that takes place outside their bourgeois bubbles. The poor Sunni youth have found an outlet away from traditional Lebanese “feudal” politics of manipulation. They now celebrate Jabhat al-Nusra and IS. To them, it now seems as if the “moderate” days of Hariri’s politics are a bygone era.

The poverty that many Tripolitanians are mired in has made education seem pointless to many of the young. However there are still some who believe in education as a way out of the warring streets. At the start of the school year last September 2014, the main gate of Dar al-Salam—Bab al-Tibani’s public middle school—was wide open for Lebanese parents to start registering their children. Inside the principal’s office, a dim room lit only by weak daylight, teachers used the flashlights on their cell phones as they searched and sorted through bundles of files of students’ records. Tripoli, like most of Lebanon, suffers daily fourteen-hour power cuts, and the public school had no electricity. One teacher proclaimed to an anxious mother there to register her teenage son Muhammad: “Your son is not among last year’s students. Are you sure he attended school last year?” Umm Muhammad Qasim had threaded her way through corridors packed by other parents and stormed into the principal’s office pleading with teachers to get her son back to school. The weary mother breathed heavily, her face dripping with sweat as she wiped her forehead and tucked loose strands of hair back into her navy blue headscarf. She lamented, “I took my son and moved away from Bab al-Tibbani last winter as war intensified. Maybe that is why you cannot find his results. I did not want his friends to lure him to join militants on the streets.” Umm Muhammad pleaded with everyone in the room, even beseeching the principal, “Please do not let my son miss school. I do not want him on the streets.” The principal, Hussam Mir, gave the weary woman a reassuring smile, and comforted her by promising, “Your son will be in class this year.” He further emphasized, “He will remain in school under my own provision.”

The middle-aged public school principal Mir believes,

the underprivileged are overlooked by all sides, especially by those who claim representation of the people of Tripoli. Families nowadays concentrate all their efforts to educate their children in professions that will secure jobs in the [Arab] Gulf. The lucky ones who get a job in the Gulf leave Tripoli and never come back. As for those who do not have degrees, whose families where not able to spend on their education, those are left frustrated and jobless. Many end up hustling on the streets for petty cash. Because many are unemployed, the broken youth of Tripoli find other outlets for their youthful energies and they end up becoming victims of drug abuse, street clashes, politics, and alcoholism.

Outside Bab-al-Tibbani public school, there unfolds a concrete jungle: a stretch of deprived underdeveloped areas of Tripoli where scowling men, young and old, line the streets beneath bullet-riddled buildings. On the walls behind them, glossy pictures of young men “martyred in Syria” are plastered over fading pictures of local politicians, while store shelves stand empty. It is not only the fact that Tripoli is an under-developed city. The problem is compounded by a complete absence of government institutions. Principle Mir has gone above and beyond his duties to try and give support to a disenfranchized youth. He explains, “After I leave office today I will start my yearly visits to philanthropists in Tripoli to collect school registration fees. The majority of families in Bab al-Tibbani cannot afford to pay the minimal charge of 90,000 Lebanese liras (sixty US dollars) per student.” The concerned school principal goes on to explain his people’s plight:

An unemployed father with five children will not send them to school if he cannot find 90,000 L.L. for each child. This is not part of my job and I would rather be at home after school hours but I also do not want people to have the slightest excuse to keep their children off school. Once a child misses one school year, street life takes over and that leads to the disintegration of the child’s personality.

Betrayed and Abandoned by Their Leaders

At the entrance of the school, a young man stands in the parking lot dressed in a yellow shirt and blue jeans, with a substantial amount of gel in his dark hair. Ahmad quarrels as his mother drags him to register for school. “I am getting you back to school whether you like it or not,” his mother snarled at him as he made his last attempts to ditch registration. The young man had missed two school years because of the war between Bab al-Tibbani and Jabal Muhsin, but his mother will not allow that to continue. Ahmad was ten when rounds of communal infighting flared in his neighborhood back in May 2008. Today it is an unavoidable part of his life. The eldest among his six siblings, he has hardened in the absence of his father. When asked why he hesitated to return to school, Ahmed responded with an air of responsibility, "I`m the man of the house now, since they conspired against us [Sunnis] and arrested my father following the last round of clashes [in April]." The past six years of Ahmad`s life have probably already shaped the rest of his life.

Ahmad’s father, like many other men in Bab-Tibbani, galvanized by big promises made by Sunni politicians, took up arms and became a militant for hire. Ahmad’s mother, who is furious about her husband`s arrest, lashes out at her son’s childish hero worship as he flicks through pictures on his phone showing him and his father standing shoulder to shoulder smiling while each holds a Kalashnikov. “Do not even think about becoming like your father. Can you not see how they fooled him, used him, and [then] abandoned him when they did not need him.” Embittered Umm Ahmad denounced the politicians: “Our zu‘ama’ (feudal leaders) lied to us, they betrayed us.” Ahmad’s father, Muhammad Amin, like many from impoverished Bab al-Tibbani neighborhood of Tripoli had been engaged in militant clashes against an equally impoverished neighboring ‘Alawi area of Jabal Muhsin: first as revenge for the 8 May 2008 clashes and later on as an act of (Sunni) solidarity with the Syrian uprising. “My husband gave all we got for Hariri’s sake, and what did Hariri give us in return? Nothing, his minimarket was turned into a bunker on the frontline, and then he started selling our home furniture and then took two pieces of gold I had to buy arms and ammunition”. Like the majority of Bab-al-Tibani’s low-income male residents, Muhammad Amin believed that giving allegiance and fighting for the Hariri-led Future Party would eventually pay off. “Each round of fighting, he sold one more piece of our household. I got angry at him, but he always told me do not fear, Saad [Hariri] will not forget about us. He will take care of us, give us jobs, and pay for our children’s education.”

Like Ahmad, many men of different ages feel betrayed by these promises and are today searching for means to draw attention to their plight. On the last weekend of August 2014, when pictures circulated on social media of a young man from Ashrafiyya (a traditionally Christian area of east Beirut) burning an IS flag, Ahmad’s friends found an outlet for their anger. According to Ahmad, “people saw the words of God being burned. This was a message—a challenge.” On that night (of Saturday 30 August), a handful of boys went to Mina, a Christian area of Tripoli, and sprayed graffiti on churches that read, “The Islamic State is coming.”

This incident with the graffiti is given little weight by Principle Mir, who stressed, “A handful of angry youth do not sum up a city of approximately one million inhabitants.” Another school teacher who was in the room interjected, “In our poverty stricken area of Bab al-Tibbani, many men have gotten used to receiving an income from politicians and today feel abandoned now that local politicians do not need them shooting at Jabal Muhsin and manning the streets. They [thus] take to provocative violent acts as reminders to embarrass the local politician who closed the faucet once he secured his share in the government.”

Many abandoned foot soldiers holding their street corners have found themselves discarded. Their purchasable efforts were once used by “moderate” politicians. In times of wars, they manned their guns. In times of peace, they herded voters to the ballot box. In these impoverished sections of Tripoli, people are forever politicized by the acts of their leaders. Now forsaken by these very same leaders, many are left with no income. They are angry and resentful.

For the last six years, the endurance of poverty-stricken Sunnis has thinned. They now realize that they were not included in political deals made in their names. Betrayed and broke, they turn to the most radical violent expressions available. Their humiliation has empowered the Sunni rhetoric of victimization that has been fed to them for years. Some of these young men do struggle to find a job in the vegetable market or live on daily wages from menial labor. However the long hours for little pay never result in a prosperous and dignified life. In despair, and loathing of those wealthy politicians who used and abused them, a broken Sunni youth in his twenties eyeballs movements or ideologies like those of IS or Jabhat al-Nusra. Islamist radical movements function as the go-to place for vengeance. This is not so much to fulfill the dream of a caliphate or to reach some phantasmic after life. Rather, it is precisely for a lost youth to have a goal in life, to retain their own dignity. It is important to note here that almost all of the suicide attacks that have struck Lebanon in the last three years were executed by young Sunni men who came from marginalized poverty hubs resembling the conditions of those warring areas of Tripoli.

Broken and Disillusioned

After rounds of political use and abuse, Tripoli’s inhabitants do not have a way out from the shifting sands beneath them. The political money that filled their bellies became a way of jailing them. Just outside a grocery store on Syria Street, two middle-aged men argued about what seemed to be a family dispute. Just twenty meters away from the quarreling men, a Lebanese army armored vehicle was parked on the side of the street. The soldier posted there started walking toward the commotion. Both men turned to the soldier shouting, “Mind your own business and go back to your spot.” One of the two men, Muhammad Zoubi, fifty-four, dressed in a beige short-sleeve dishdasha, was trying to get his cousin, the owner of the grocery store, to let him buy a gas cylinder on credit. His cousin refused, arguing that Muhammad already owed him 120,000 Lebanese liras from last month. Muhammad, a father of four, has been unemployed for the last two years. A former member of the Future Party, he had originally joined the group in hopes of scoring a security-guard part-time job, getting financial aid to help cover his children’s education, and—as a last resort if need be—to benefit from the food rations the party used to distribute at the end of every month. “One needs political connections in Lebanon and Future used to be our people.”

Today, Muhammad resents Future Party and denounces them as “a group of corrupt men robbing their own people’s charity.” Chain-smoking Muhammad recalled and loathed those who caused his plight:

Following (Rafiq) Hariri’s assassination, Sunnis in here felt orphaned so we put all of our trust behind Saad [Hariri] to lead. Since then Saad has repeatedly deceived us. He is no Rafiq [Hariri- the father of Saad]. The Future Party made promises of medical care, jobs, and education for those who supported and voted for the party. But, as time passed, we received bread crumbs. We watched Future’s higher-up members get richer while we sank deeper into poverty. In 2008, Future leaders told us we needed to send men to Beirut to defend Sunnis there from Hizballah and their allies. We rushed to support and defend our Sunni brethren in Beirut. Once in Beirut, they gave us wooden sticks to face the waves of armed militants from 8 March marching all over Beirut. We ran away like rats. This was a strong blow to us. It humiliated us. We were used as pieces of wood in Saad’s big fire. Other Sunni politicians played us the same way when Hariri ran away in 2011. Najib Miqati, Mohamad Safadi, and today Ashraf Rifi played on our Sunni sentiments and used us in rounds of clashes against our ‘Alawi neighbors. Now, since they all fixed themselves in the government, they have washed their hands clean of us.

Many men from different ages in Tripoli take refuge in violence as a reminder to others that they are present. They are angry. However, violence becomes a way of life. It brings street credibility, self-confidence, and respect to those who have been socially alienated for being uneducated, constantly broke, and not fit for the social standards set by the wealthy. In one of the poorest cities on the Mediterranean Sea, prosperity is nowhere in sight for the vast majority of its half a million residents. “We are so cheap. That is what makes it easy for politicians to buy us,” Zoubi says. “They throw us a hundred dollars and we turn into chess pieces in their game. I do not blame young men joining Salafi movements like Jabhat al-Nusra at least these are real Muslims, they do what they say.”

A United Nations Development Program (UNDP) field survey of the living conditions and mother and child health in Bab al-Tibbani and Jabal Muhsin in Tripoli contains shocking figures. Around twenty percent of men and 91.5 percent of women are unemployed. The high early-school dropout rates, especially for boys, mean the illiteracy rate for young men (fifteen to twenty-nine years) at twenty percent, the highest in Lebanon. The study also shows that 9.3 percent of the population suffers from illnesses that remain untreated due to lack of money or absence of the required specialization or treatment in neighboring dispensaries.

One of many broken youth of Tripoli is Samir, a twenty-two year old unemployed male who has never managed to learn a craft since he left school at the age of fifteen. Samir tries to maintain his looks as best as he can by sporting a black t-shirt tucked into old blue jeans draped over shiny black pointy shoes. He holds a tablet at his side which he insists on calling a “phone and computer.” Samir hovers around the streets of Tripoli looking to score a ten or twenty to cover his daily expenses of tea, coffee, one meal, and tobacco. He admits to being unskilled: “I never learned a craft, and hated every job I tried to learn. I just wanted to make money.” But today, he is willing to find a fixed job even for low pay. “I hate being on the streets people take advantage of my services, I also hate being broke.” Self-inflicted cuts on his forearms have become thick strips of scars; crisscrossed and overlapping they resemble the haphazard electricity wires entangled above were we meet on one Bab al-Tibbani street. These scars on his arms reflect his self-harming habit; he and many of his friends began this self-harm as a way to express their “rage.” Samir’s rage has never left him, his scars have only grown thicker. “It is better I take it out on myself instead of hurting others,” he sighed. He then asked if I wanted to buy his tablet.

As we walked down the street to the coffee cart parked on the corner, Samir joked, “I am inviting you but you are paying.” We sipped our coffee, Samir put two cigarettes in his mouth lit them both and passed me one of the long Cedars, a cheap Lebanese brand that pops tiny sparks while burning. From behind a cloud of smoke Samir illustrated his options, “Three solutions are left for me and the youth in this neighborhood: immigration by sea to Europe—if I could find three thousand dollars; find a wasta [connection/favoritism] and get enrolled in the army or police force, receive a fixed salary, and get married. Or, if these two options do not materialize, then joining IS or Jabhat al-Nusra, but only if they pay. There is nothing else I have not tried.” He goes on to explain resentfully, “We have already tried being dogs for our local politicians for pocket money and in the hope that through a politician’s connections one will finally get a job in the al-Amn al-Dakhili (Internal Security Forces). But after twenty rounds of fighting, we realized that those promises are only lies.”

Streets Hijacked by Violence

Up until April 2014, which featured the last round of fighting between Jabal Muhsin and Bab al-Tibbani, militant groups fighting in Tripoli varied in numbers as their funding fluctuated as much as their loyalties did. Some of these so-called axis leaders led militias made up of as little as five fighters whereas others swelled up to four hundred fighters. Their firepower also varies. They all fire machineguns, hand grenades, and RPGs, but the bigger groups also use mortars. Politicians who fund these groups usually keep them as muscle for personal protection or as an entourage in times of elections—to hang posters and generate and recruit voters. Ultimately the majority of these militant groups turn into proxies for regional powers that financially or/and politically support this or that politician in Tripoli. In the latest wave of clashes with the Lebanese army, only two factions clashed with the army: the two groups loyal to Jabhat al-Nusra and IS led by emerging young enthusiasts on the Tripoli Sunni militant scene: Shadi al-Mawlawi and the imam of the Haroun mosque, Shaykh Khalid Hubals.

Today young men led by the power trip of this extremist ideology and violent expression govern the streets. As I walked out from Bab al-Tibbani public school on that muggy September 2014 morning, angry condemnations could be heard from the school’s entrance. Around two-hundred meters down the street, white-haired men gathered and veiled elderly women wailed in resentment: “May God curse their fathers.” Seniors from the neighborhood had gathered to denounce the killing of a young man that took place the previous night. “He was one of the good ones, a decent young man who respected all and was respected by all,” lamented one man in his sixties. “Shame on these provocateurs,” murmured the others in the gathering. Another victim of sectarian violence, Fawwaz Bazi, whose family originated from south Lebanon, was born, bred, and finally killed in Bab al-Tibbani. Guilty for being Shi‘i, according to the victim’s neighbors, he was taken to Tartousi mosque where he was beaten up, interrogated and accused of being a Hizballah operative. Later that night, he was found on the outskirts of Bab al-Tibbani shot and left to bleed on the Abu Ali motorway. His attackers had fired one bullet into his foot and another into his crotch that made its way out through his chest. Fawwaz Bazi died a few hours later in the hospital. The saddened and angry residents were suddenly dispersed by the arrival of two men, both with shaved heads and with unkempt beards. In their mid twenties both men wore khaki military pants and black t-shirts and had a visible pistol tucked into their waists. The gathering crowd seemed to recognize the bearded men and slowly departed. In a dim alley where we had retreated and could not be overheard, one man reported that these thugs belong to Shadi al-Mawlawi and that “they killed him.”

.jpg)

[Last September as I was going to el-Mina I stumbled upon Tripoli’s beautifier Ali Rafei.

The local artist was putting his final touches on his latest portrait in Tripoli of a smiling migrant worker.

See original here: https://www.facebook.com/Ali.Raf3i]

A Stable Tripoli: A Utopian Conception?

The harshness of circumstances in Tripoli has created an atmosphere of despair: many of its youth gone to Beirut or abroad. The city is not, yet, depleted of its creative youthful energies though. Those determined ones who remain struggle to bring back stability to their city.

The situation in Bab al-Tibbani, like other impoverished sections of Tripoli, is a grim reality that continues to deteriorate exponentially with no concrete solutions in sight. Residents of these impoverished sections have been at the mercy of politicians and their political adventures. Hopeful but disillusioned Principle Mir says, “Even after all the murdering and infighting people are still willing to abandon violence if they were offered other economical solutions.” The school principal says, “People want jobs, they want to lead an honorable life, a normal life.”

Walking away from Bab al-Tibbani disoriented by the complexities of its grim reality the scenes switch rapidly. From decaying buildings riddled with RPG and bullets marks to wide promenades lined by shiny Mercedes-Benzs, Range Rovers and BMWs parked under tall buildings guarded by the local Internal Security Forces. There, in that middle-upper-class bubble of Tripoli on Ma‘rad Street, where many of Tripoli’s polity reside, I met Chadi Nachabe. Nachabe is a thirty-year-old smiley young man who coordinates a local NGO named Utopia. Their motto reads, “Dedicated to abolishing all types of social discrepancies through community development projects.” In Tripoli, this is not only a tough task for a youth to undertake but a utopian dream. As we sat in Utopia’s modest office, a team of young women and men buzzed with activity. Phones rang and the utopian volunteers responded coordinating a joint relief campaign for Syrian refuges and their Lebanese hosts; organizing tutors to support students in passing official exams; linking youth from Bab al-Tibbani with private sector companies for internships. Last but not least, as the school year approached, three hundred children, from impoverished areas whose families cannot afford to send them to public schools, are being listed by Utopia’s volunteers and their registration fees covered. Sitting on top of the utopian hive, Nachabi emphasizes the urge for their NGO work: “In my opinion Tripoli is a socio-economical problem not an ideological or sectarian problem. Problems in impoverished areas of Bab al-Tibbani and Jabal Muhsin are economic and security issues. The Lebanese government is nonexistent.” In a functional state, the social care initiatives, responsibilities, and rehabilitation efforts undertaken by the young Tripolitan volunteers are usually the sole responsibility of state institutions. In Lebanon’s dysfunctional state, having minimal services is a luxury for those who can afford it. It goes without saying that if there was a will on the part lawmakers or the state, social problems in Tripoli could probably be fixed.

Utopia, with its minimal resources and the energy and effort of its youth, was able to embark on an initiative that reaches out toward those most dehumanized: the militants. Nachabi explained their approach: :We managed to equip street fighters with tools to find other ways of life. Many of those militants found jobs, saw another way to life and quit their guns. Out of those eighty-nine militants there are sixty-three who got engaged and are looking to start a family."

However, the majority of disenfranchised youth continue to be on the streets, jobless, with the delirious power trip they get from the militias giving them purpose in life. “If there were socioeconomic projects that brought job opportunities, believe me, they would abandon those militant organizations. Most of these youth want to live like the rest of us.” The son of his city, Nachabi is disheartened with the severity of and complexities that riddle Tripoli. With frustration he explained,

I think the Lebanese government is incapable of doing anything about the militants because the government takes into consideration the regional power that backs up those groups, for example they will not arrest al-Nusra activists, or supporters, because they know al-Nusra is backed by Qatar. The Lebanese government wants to keep good relations with Qatar. In addition, this division and conflict exists inside the Lebanese government where you find one intelligence branch supports Syria’s regime and another like the Information Branch is against the regime; and this translates in Bab al-Tibbani to armed groups some of whom are backed by the military intelligence and others by the ISF Information Branch. Eighty-Five thousand residents inhabit Bab al-Tibbani, one thousand are armed and maybe nine hundred out of those are only armed to protect themselves. The one hundred left are the so-called extremists and these control not only the fate of Bab al-Tibbani but the whole city of Tripoli with its half a million residents.

For the last six years, political violence has hijacked Tripoli and further alienated it from the rest of Lebanon. The millionaire and billionaire politicians who control the fate of the city have spent millions of dollars in ammunition shot by one poor community killing and besieging another impoverished community. The general mood in Lebanon is one of apathy toward its second capital. Yet still there are few who are trying to make a difference and highlighting this ongoing injustice. The local Tripolitan artist El-Rass sums up the brutality of life in his city and its inevitable consequences in the lyrics of his song “In Tripoli’s Castle”:

Security tensions, I am afraid I might find a Salafi in the mirror. I’m afraid that my aim in the end will be to seek protection from hearts filled with injustice and deprivation, from minds shunned from dreams and education/ immersed in starvation and the commerce of religions

. . .